Confession in the Scriptures & Early Fathers

The Sacrament of Confession, also called Penance or Reconciliation, is considered one of the Sacraments of Healing in the Church (along with the Anointing of the Sick). While Baptism (one of the Sacraments of Initiation) conveys the forgiveness of sins, original and actual, it does not prevent the baptized person from committing any future sins, nor do its effects automatically forgive any future sin we may commit. For forgiveness of sins committed after baptism, the Christian has recourse to the Sacrament of Confession.

If the Eucharist is the regular meal of the Christian (our daily bread), then Confession is like our daily bath. It is a Sacrament that the Church encourages us to take advantage of often. The Pope himself maintains a regular schedule of weekly confession.

As mentioned earlier, this sacrament is called by different names, each one referring to some aspect of the sacrament. Confession refers to the fact that the penitent audibly confesses his particular sins. Penance refers to the penance that the priest assigns us, as satisfaction for our sins. Reconciliation refers to the end result of our confession and forgiveness, our reconciliation with God. This sacrament is also called the Sacrament of Conversion, since through it we turn away from our sins and towards God.

For most non-Catholics, it is the act of audibly confessing our sins to a priest that they find objectionable. Let us, then, walk through Scripture to see just where this practice began.

And just then some people were carrying a paralyzed man lying on a bed. When Jesus saw their faith, he said to the paralytic, “Take heart, son; your sins are forgiven.” The some of the scribes said to themselves, “This man is blaspheming.” But Jesus, perceiving their thoughts, said, “Why do you think evil in your hearts? For which is easier, to say, ‘Your sins are forgiven,’ or to say, ‘Stand up and walk’? But so that you may know that the Son of Man has authority on earth to forgive sins” – he then said to the paralytic – “Stand up, take your bed and go to your home.” And he stood up and went to his home. When the crowds saw it, they were filled with awe, and they glorified God, who had given such authority to human beings.

Matthew 9:2-8

In this passage, the Jewish scribes are troubled by Jesus’ claim to be able to forgive sins. They understand, and correctly so, that only God has the authority to forgive us our sins, since our sins are ultimately committed against God. What they fail to understand is that Jesus is God, and as the Second Person of the Holy Trinity, possesses this divine power to forgive sins. On that level, this passage is an affirmation of the divinity of Christ. On another level, however, this passage also indicates that God has given this authority “to human beings.” Christ’s divinity, joined now for all of eternity with human flesh, has enabled human beings to participate in this divine ministry of Christ, the ministry of forgiveness, as we shall now see.

After the Resurrection, before Christ Ascended into heaven, He said to the Apostles:

“As the Father has sent me, so I send you.” When he had said this, he breathed on them and said to them, “Receive the Holy Spirit. If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven them; if you retain the sins of any, they are retained.”

John 20:21-23

Before, we read that Christ explicitly has the authority to forgive sins, and it is implied that this authority is, or will be, inherited by humanity. In this passage, we read now where Christ, having the authority to forgive sins, expressly passes this authority on to the Apostles, the first leaders of the Church. If the Apostles are to be able to either forgive or not forgive people’s sins, of course they would have to have some way of knowing what those sins are. Thus the need for auricular confession. Unless a penitent comes before a minister of Christ’s Church and confesses his particular sins, that minister will not know what sins to forgive or retain.

All this is from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ, and has given us the ministry of reconciliation; that is, in Christ God was reconciling the world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them, and entrusting the message of reconciliation to us. So we are ambassadors for Christ, since God is making his appeal through us; we entreat you on behalf of Christ, be reconciled to God.

2 Corinthians 5:18-20

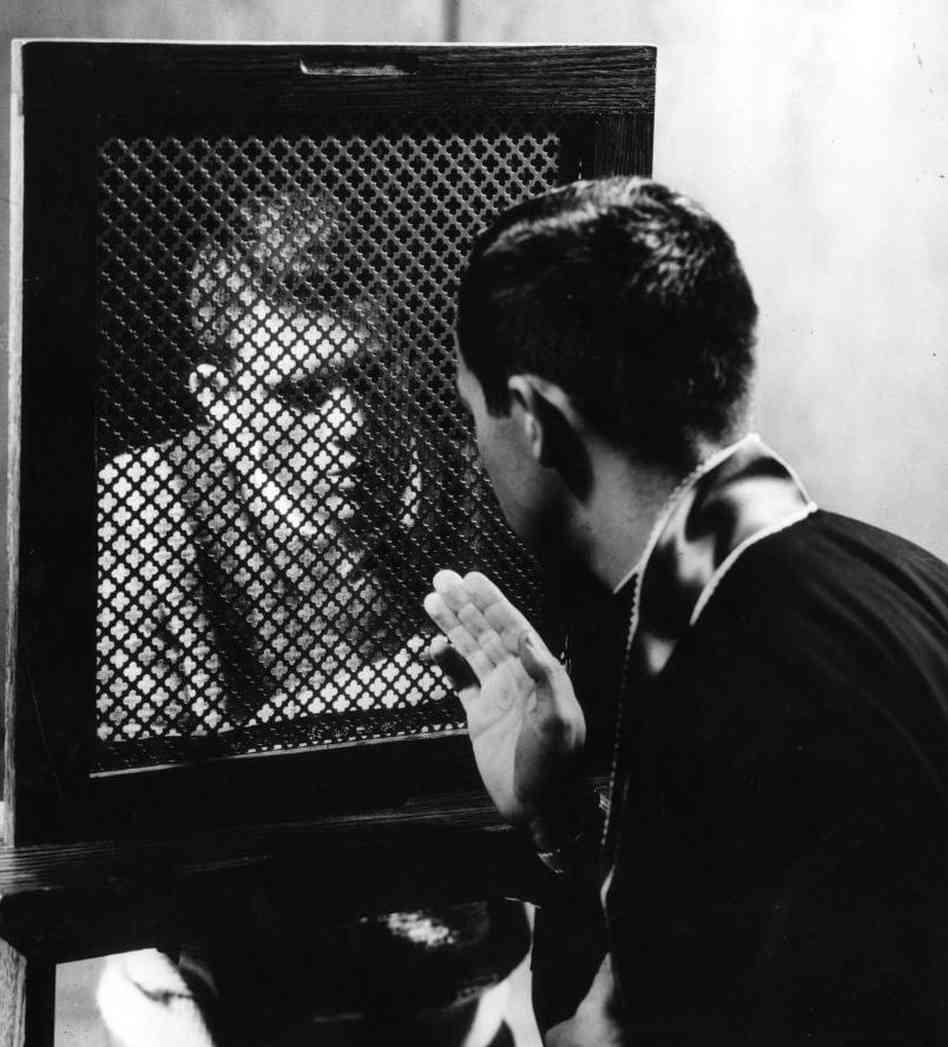

Here we read St. Paul very clearly speaking of the “ministry of reconciliation.” This ministry, he says, God has given to us. It is not a ministry that belongs to God alone, as some Protestants believe, and as the pre-Christian Jewish community we encounter in Matthew’s Gospel above understood. God has deemed to share this ministry with His Church. This does not mean that the ministers of the Church have this authority by their own right. No, the authority to forgive comes only from God. But, as St. Paul says, “we are ambassadors for Christ, since God is making his appeal through us.” As with all the other Sacraments, the priest is simply standing in persona Christi, that is, in the person of Christ. In the confessional, it is Christ who forgives you, through His ministers.

Are there any among you sick? They should call for the elders of the church and have them pray over them, anointing them with oil in the name of the Lord. The prayer of faith will save the sick, and the Lord will raise them up; and anyone who has committed sins will be forgiven. Therefore confess your sins to one another, and pray for one another, so that you may be healed.

James 5:14-16

James here speaks of the prayers of church “elders.” The Greek word that is translated as “elder” in the New Testament is prebytoi, which is where we get our English word “presbyter” or “priest.” James is again confirming what we have seen in other places in the New Testament. That Christ left the authority to forgive sins to His Church, His priests, who are His vicars. So “confess your sins to one another” James implores us, “so that you may be healed.” For is there is no confession, there can be no forgiveness.

The earliest Christian instructional document that we have, outside of the New Testament, is the Didache, also called The Teachings of the Apostles, written about the year 70 AD. In it, we read that we are to “confess your sins in church.” For those that think audible confession was a trick of the Catholic Church dreamed up in the Middle Ages, they only need to read the writings of the Early Church Fathers to be corrected.

Tertullian, in the year 203, speaks of a problem that many today still have going to confession. It’s like going to the doctor. It doesn’t seem to be a pleasant matter, and our tendency is to avoid it whenever we can. Yet if we are sick, we need to see the doctor, and we cannot be healed otherwise. Tertullian writes, “[Regarding confession, some] flee from this work as being an exposure of themselves, or they put it off from day to day. I presume they are more mindful of modesty than of salvation, like those who contract a disease in the more shameful parts of the body and shun making themselves known to the physicians; and thus they perish along with their own bashfulness” (Repentance 10:1 [A.D. 203]).

One of the great Easter Fathers of the fourth century, John Chrysostum (whose name means “golden tongued”) has this to say. “Priests have received a power which God has given neither to angels nor to archangels. It was said to them: ‘Whatsoever you shall bind on earth shall be bound in heaven; and whatsoever you shall loose, shall be loosed.’ Temporal rulers have indeed the power of binding; but they can only bind the body. Priests, in contrast, can bind with a bond which pertains to the soul itself and transcends the very heavens. Did [God] not give them all the powers of heaven? ‘Whose sins you

shall forgive,’ he says, ‘they are forgiven them; whose sins you shall retain, they are retained.’ What greater power is there than this? The Father has given all judgment to the Son. And now I see the Son placing all this power in the hands of men [Matt. 10:40; John 20:21–23]. They are raised to this dignity as if they were already gathered up to heaven” (The Priesthood 3:5 [A.D. 387]).

Today, people who deny that the Church has any authority to forgive sins no longer go to the priest for confession. “I confess my sins directly to God,” they say, “and He forgives me.” And then they pay hundreds of dollars to a psychiatrist who will sit and listen to their sins.

The Protestant has it half right. If you are truly sorry for your sins, God will forgive you, even if you do not confess your sins to a priest. Remember, God made the Sacraments for our benefit, but He Himself is not bound by them. This act of being “truly sorry” for one’s sins is what the Catholic Church calls perfect contrition. The Catechism teaches, “Such contrition remits venial sins; it also obtains forgiveness of mortal sins if it includes the firm resolution to have recourse to sacramental confession as soon as possible” (CCC 1452).

What this means is that if someone is perfectly contrite, that contrition itself brings about the forgiveness of sins. But, if someone is really perfectly contrite, they should also be moved to seek out sacramental forgiveness in the confessional. Otherwise, there is the danger of “fooling oneself” into believing you do not need the sacrament. This is what the entire Protestant movement has done, by doing away with sacramental confession altogether.

The Catholic Church teaches that even imperfect contrition is sufficient for sins to be forgiven in the confessional. If you are repentant enough to come to confession, that shows that your heart is at least seeking reconciliation with God, and God will not keep Himself from those who seek Him.

SATISFACTION FOR SINS

Many non-Catholics also object to the performance of penance associated with this sacrament. They see it as some kind of “works-salvation” that they object to. Remember that “penance” and “repent” have the same root word. Christ calls each of us to repent. If to repent means to “turn around,” then penance is the act of that turning.

To properly understand why we need to perform acts of penance as satisfaction for our sins, we need to first understand just what sin is, and what its effects are. A sin is a breaking of a relationship. Our sins not only harm our relationship with God, but many of them also harm our relationships with our neighbors, and even with ourselves.

Absolution means that we are forgiven of our sins, but it does not take away all the negative effects of the sin itself. You cannot steal money from someone, confess that sin, and expect to keep the money. Remember that God is not only perfectly merciful, but also perfectly just. Justice requires some satisfaction for our sins to be made.

If you are playing baseball in my back yard, accidentally hit the ball through my window, and come up to me and apologize, I’ll probably forgive you. I know it was an accident, and I won’t be mad at you. You are forgiven. But my window is still broken, and someone needs to pay to fix it. Justice requires that since you broke it, you fix it.God is perfectly merciful, and so He will always forgive us if we come to Him with a contrite heart. But God is also perfectly just, and so expects us to make proper atonement for our transgressions.

And “prescribed” is a very good way of looking at the penance assigned to you by your confessor. Just as the doctor may prescribe a particular medicine for your physical healing, the priest prescribes the medicine of penance for your spiritual healing. This proper understanding of penance also can help one come to grips with some of the more “controversial” Catholic doctrines, such as purgatory. If we have been forgiven of our sins, then we are not condemned to eternal damnation when we die. But we must also perform just satisfaction for our sins before we enter heaven. If we have not done proper penance on earth, we must complete the satisfaction for our sins in purgatory (where we are “purged” or made pure, before we enter heaven).

The Sacrament of Confession, though avoided by many Catholics today, and abandoned completely by Protestants, is a Sacrament of God’s Love and Mercy. G. K. Chesterton, when asked why he became a Catholic, replied, in his usual witty manner, “To get my sins forgiven.”