The Parable of the Dishonest Steward

25th Sunday of Ordinary Time

This Sunday we continue reflecting upon the parables Jesus tells in Luke’s gospel with the parable of the dishonest, or unjust, steward (Lk 16:1-13). Parables are stories told to illustrate a lesson, like the parables of the lost sheep and the prodigal son that we heard in the gospel last week. But the lesson Jesus is teaching with this parable might seem unclear to us at first.

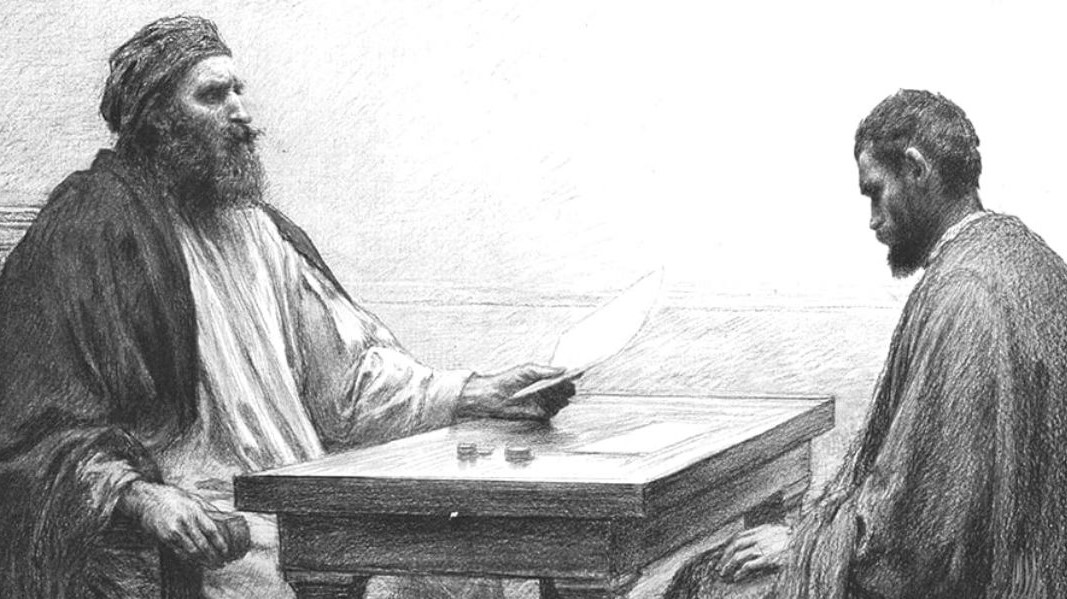

The story is about a steward — one who has responsibility for the care of another’s property — who squanders his master’s wealth. His master discovers that his property is being mismanaged, so he summons the steward to give an account. The steward knows that the gig is up and he’s likely to be tossed out on the street! So before he goes to report to his master, he visits all his master’s debtors — that is, anyone who owes money to his master — and he writes them false promissory notes to make it look as though they owe much less than they do. It’s a rather dishonest form of debt relief! His purpose in doing this is to set himself up so that when he’s out of a job, he’ll have people he can ask for favors. Sounds like a great guy, right?

Now we come to the confusing part of the parable. Jesus never says that this dishonest steward repents or has any remorse for the way he is cheating his master. And yet, the master commends him for acting prudently! So is Jesus saying we should be like that dishonest steward, mishandling our responsibilities and willing to cheat someone else if it works for our benefit? Not hardly. So what’s the point of this parable?

Jesus is using a rhetorical technique that involves an argument from lesser to greater. It’s a way of saying, “If this lesser thing is true, then this greater thing is even more true.” Here, the lesser part of the argument is the way the dishonest steward manages his master’s wealth, squandering it to his own advantage. His dishonesty is not praiseworthy. What the master finds praiseworthy about his behavior is the prudence he shows in planning ahead for his future.

The point Jesus is making is that if even dishonest people act prudently in regards to their future, how much more prudently should honest and just people act in regards to theirs. This is the greater part of the argument. The “children of light” Jesus mentions in verse 8 are the elect of God who are called to share God’s eternal life in heaven, as opposed to the “children of this world” who place their trust in material wealth. How much more, Jesus is saying, should his followers be prudent in managing the goods that our Master, God the Father, has entrusted to us.

We are all stewards. Everything you and I possess — our material goods, our wealth, our gifts and talents, our bodies and our souls — really belong to God. He entrusts us with these gifts, but there will come a day when we must give an account for them. Are we at least as prudent as the dishonest steward in the parable when it comes to planning for that day and the account we will have to give before our Divine Master?

For, “if you are not trustworthy with what belongs to another,” Jesus ends this parable, “who will give you what is yours? No servant can serve two masters… you cannot serve God and mammon” (Lk 16:12-13). What is mammon? Scholars have suggested that this word derives from a Hebrew phrase meaning “that in which one trusts.” If you trust in your wealth and material possessions, you are, in effect, making a false god of your possessions. Faithful disciples understand that their wealth (material or otherwise) is not their own and place their trust instead in God. Being a good steward of God’s gifts means using what we have been entrusted with not only prudently, but charitably, sharing our resources freely with others, so that when we are called to give that final account to our Master, we might hear the words, “Well done, good and faithful servant” (Mt 25:23).