Letting Go

28th Sunday of Ordinary Time (B)

This Sunday’s gospel reading contains what I think is one of the saddest passages in scripture. It is the encounter between Christ and the rich young man (Mk 10:17-22). Here we have a man who seems to have it all. He has youth. He has wealth. He is a man of good character and moral virtue, having obeyed God’s commandments all of his life. He comes before Jesus and asks the most important question any of us can ask: “What must I do to inherit life?” (Mk 10:17). He’s asking the right question, and he’s asking the right Person. It seems like he’s got everything going for him. What could go wrong?

Jesus tells the man that he only lacks one thing: “Go, sell what you have, and give to the poor and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me” (Mk 10:21). The last thing we are told about this man who seemed to have it all is that “he went away sad, for he had many possessions” (Mk 10:22).

Why are possessions so dangerous? Owning property is not bad in itself. The scriptures presuppose a right to private property, in the commandment against theft (Ex 20:15). If we didn’t own things, we wouldn’t have the means to take care of ourselves or our families, which the scriptures say we have an obligation to do (1 Tim 5:8). The scriptures also say “the laborer deserves his wages” (1 Tim 5:18). Yet in the same letter that St. Paul says that, he also says, “The love of money is the root of all evil” (1 Tim 6:10).

Jesus is clear on this point. When he speaks of the poor, he offers them a blessing: “Blessed are the poor” (Lk 6:20). When he speaks of the rich, he offers them a warning: “It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for one who is rich to enter the kingdom of God” (Mk 10:25).

If owning possessions is not objectively sinful, why is owning too many possessions so spiritually dangerous? It’s because we run the very real risk of our possessions possessing us. The rich young man is an illustration of this. Jesus gave him a clear choice: do you want your stuff or do you want me? The rich young man chose his stuff, and he went away sad. Even if he was happy with his wealth (he wasn’t, which is why he came to Jesus asking what he must do), how long would his riches have kept him that way? We are told he was a young man, so maybe another 40, 50 or 60 years? But then what? You can’t take it with you.

Jesus was offering this man the only kind of happiness that you can take with you, which is happiness that comes from union with God. He was asking the man to trade his few years of natural happiness for an eternity of supernatural happiness. What a bargain! But the rich young man turned it down. We can do stupid things in the service of wealth. St. Paul says, “Those who want to be rich are falling into temptation and into a trap and into many foolish and harmful desires” (1 Tim 6:9).

The Camel & the Narrow Gate

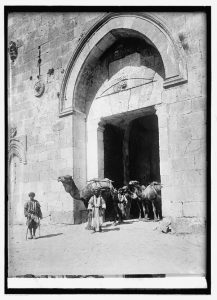

After the rich young man goes away sad, Jesus uses the opportunity to teach his followers an important lesson. He says, “It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for one who is rich to enter the kingdom of God” (Mk 10:25). It seems like such a ridiculous image. A camel passing through the eye of a needle is impossible, right? But Jesus is actually describing something that would have been familiar to any visitor to Jerusalem.

Like many ancient cities, Jerusalem was protected by high walls with gates that could be closed at night for security. After the gates were closed, entrance was only possible through smaller doors in the gates. One such door leading into Jerusalem (which is often used in the scriptures to symbolize heaven) was known as “the eye of the needle” because it was so narrow. Remember when Jesus says to “enter through the narrow gate” (Mt 7:13)?

Camels are wonderful beasts of burden which were widely used by travelers and merchants to carry heavy loads through the desert. But if a merchant showed up after hours with a camel laden with goods, he would find it impossible for his camel to enter through that narrow gate so burdened. To gain entry into the city, all of his possessions would have to be unloaded from the camel and carried through by hand. Only when it was stripped of its burden could the camel pass through.

Jesus is telling us what we must do to pass through that narrow gate into the heavenly Jerusalem. We have to unburden ourselves. We have to let go of our attachments to the things of this world before we leave it. “For we brought nothing into the world, just as we shall not be able to take anything out of it” (1 Tim 6:7).

A disordered attachment to possessions and material wealth can be especially tempting (and you don’t have to be “rich” to have an unhealthy attachment to possessions). But material goods are not the only things we can be attached to. We can have a disordered attachment to our pride, to power, to fame, to comfort, or to our need to be right.

The Great Divorce

Perhaps the best literary illustration of this in modern times is C. S. Lewis’ short allegory, The Great Divorce. The “divorce” referenced in the title is the separation between heaven and hell, the two destinations each of us must choose between at the end of our lives. In this tale, the protagonist encounters several ghosts in the afterlife who are given the opportunity to leave the miserable gray city they occupy (purgatory for those who leave it; hell for those who remain) and climb the beautiful mountain that leads to God. Before they can make that journey, however, they have to unburden themselves of anything they are holding onto that doesn’t belong in that heavenly kingdom.

One ghost is clinging to lust; another to the quest for profit. One can’t let go of his own cynicism and mistrust; another of his need to think himself better than others. Some burdens the ghosts cling to may surprise you. A grieving mother who lost a young son cannot let go of her own grief. A theologian cannot let go of his desire to study God objectively, from a distance. A self-conscious ghost cannot let go of her own embarrassment.

Each of these ghosts are given the same choice that Jesus gives the rich young man: let go of these things you are holding onto and follow me. And like the rich young man, when they find they cannot let go, they go away sad, back to the eternal gray city where they will miserably cling onto their false idols forever. But that did not have to be their fate, and it does not have to be ours. That is the point of The Great Divorce and the point of Jesus’ warning about the camel passing through the eye of the needle. It’s not impossible to enter through the narrow gate; we just need to unburden our camel.

So what are you clinging onto in your quest for happiness? What have you made into your treasure in this life? Whatever it is, Jesus is making you the same offer as the rich young man; literally the offer of a lifetime. Let it go. Unburden yourself. Follow me, and you will have eternal treasure in heaven.