Where We Got the Bible

As Christians, we believe that God has revealed Himself to man. We also believe that the Bible is the inerrant written record of that Revelation. What is the Bible, where does it come from, and why do we, as Catholics, hold it to be inerrant?

The word “Bible” comes from the Greek word for “book.” The Bible is our sacred book. The Jewish people had a variety of sacred books they believed to be divinely inspired. Christ and the Apostles confirmed this by basing their teachings on these sacred books. These books make up the Old Testament. The teachings of the Catholic Church are handed on from the Apostles, who learned them from Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit. This is what is referred to as the Deposit of Faith, and this has not been added to or taken away since the beginning of the Church. Some of this teaching has been committed to writing, and this constitutes the New Testament.

THE HISTORY OF THE BIBLE

The Jewish people had many books that they considered holy and inspired. Sometime during the third century BC these began to be compiled. There are several early compilations, but the one adopted by the first Christians, and the Catholic Church, was called the Septuagint, or Alexandrine, version, and was a translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek. During the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285-246 BC), Jewish scholars met in Alexandria to translate the entire Jewish bible into Greek, which was the common language of many Jews throughout the Mediterranean and Palestine. There were 70 or 72 translators, six from each of the twelve tribes of Israel. This is why we call their work the “Septuagint,” which comes from the Latin word for 70.

Though other translations of the Jewish scriptures existed, this was the one used by Jesus and the writers of the New Testament. Over 300 of the Old Testament quotes found in the New Testament come from the Septuagint. This is not surprising, as the New Testament was written in Greek, and it is only logical that the writers would use the Greek Jewish scriptures.

The Septuagint contains 46 books. The current Hebrew cannon only has 39, however. This is because the Hebrew canon was not formally established until around 100 AD by Jewish rabbis in the Palestinian city of Jamnia. This may have been in reaction to the growing Christian church, which these rabbis rejected. They left out seven books that are found in the Septuagint. These are Wisdom, Sirach, Judith, Baruch, Tobit, and 1 and 2 Maccabees (as well as parts of David and Esther). They did this chiefly because they could find no extant versions of these books in Hebrew, from which the Greek was translated. They had four criteria that they used to determine which books were included in the cannon: 1) they were written in Hebrew, 2) they were in conformity with the Torah, 3) they were older than the time of Ezra (400 BC), and 4) they were written in Palestine. Christians, however, continued to use the Septuagint version that Christ and the Apostles had used.

Along with the Jewish scriptures, there were many other books being circulated and used as sacred texts among the early Christians. These were mainly gospel accounts and letters of St. Paul and other Apostles. Some of these books would come to be our New Testament. The New Testament books were written between 50 AD and 100 AD, and there are 27 in all. Why did these books get included in the canon of Sacred Scripture and others, like the Gospel of Thomas and the letters of Barnabas, not? The Church herself would use her infallible teaching authority to determine which books did and did not belong in the Bible.

The first bishop to compile a list of inspired books was Mileto of Sardis in 175 AD. Other bishops also kept lists of inspired books (texts which were allowed to be read from during the liturgy), but nothing formal was done until the fourth century. In 382 Pope Damasus, prompted by the Council of Rome, issued decree listing the 73 books that have made up our Old and New Testament ever since. The Catholic Church declared these 73 books to be the Christian Biblical canon at the Council of Hippo in 393 AD, and then again confirmed this in the Council of Carthage in 397 AD. Pope St. Innocent I officially approved this same list of 73 books in 405 AD and forever closed the canon of the Christian Bible. These books were considered divinely inspired on the authority of the Catholic Church. This was to be held uncontested as the Christian canon until the 16th century.

Sometime before the end of the second century, at least one Latin translation of the whole Bible existed based on the Septuagint and Greek manuscripts of the New Testament. This is called the Vetus Itala, or Old Latin text. By the late fourth century, it was discovered that the Old Latin Bible had variations in the text from one church to another, and a unified version was desired. Pope Damasus authorized St. Jerome to revise the Old Latin text to this end. Jerome used the Greek manuscripts of the Old and New Testament to correct errors in the Latin text and re-translated sections to provide a better sense of the original meaning.

While doing this translation, he became convinced that the Western Church needed a new translation directly from the Hebrew of the Old Testament. He began this work in 390 and ended in 405 AD. It took some time for this translation to take hold, but it gradually gained acceptance over the Old Latin version. By the sixth century it was in general use by much of the west and by the ninth century it was more or less universal among the Latin Church (the Eastern, or Greek Church, of course using the original Greek Septuagint and New Testament, since that was the liturgical language of the Church there). By the thirteenth century this new Latin translation was being referred to commonly as the Vulgate (a title that used to belong to the Old Latin text).

The advent of the printing press greatly affected the history of the Bible. The first printing of the Vulgate Bible was done by Gutenberg in 1456, but other editions came out rapidly. The circulation of other Latin versions of the Bible caused uncertainty as to which was the standard text. This caused the bishops at the Council of Trent in the sixteenth century to declare the Vulgate alone to be “authentic in public readings, discourses, and disputes, and that nobody might dare or presume to reject it on any pretence.”

PROTESTANT VERSIONS

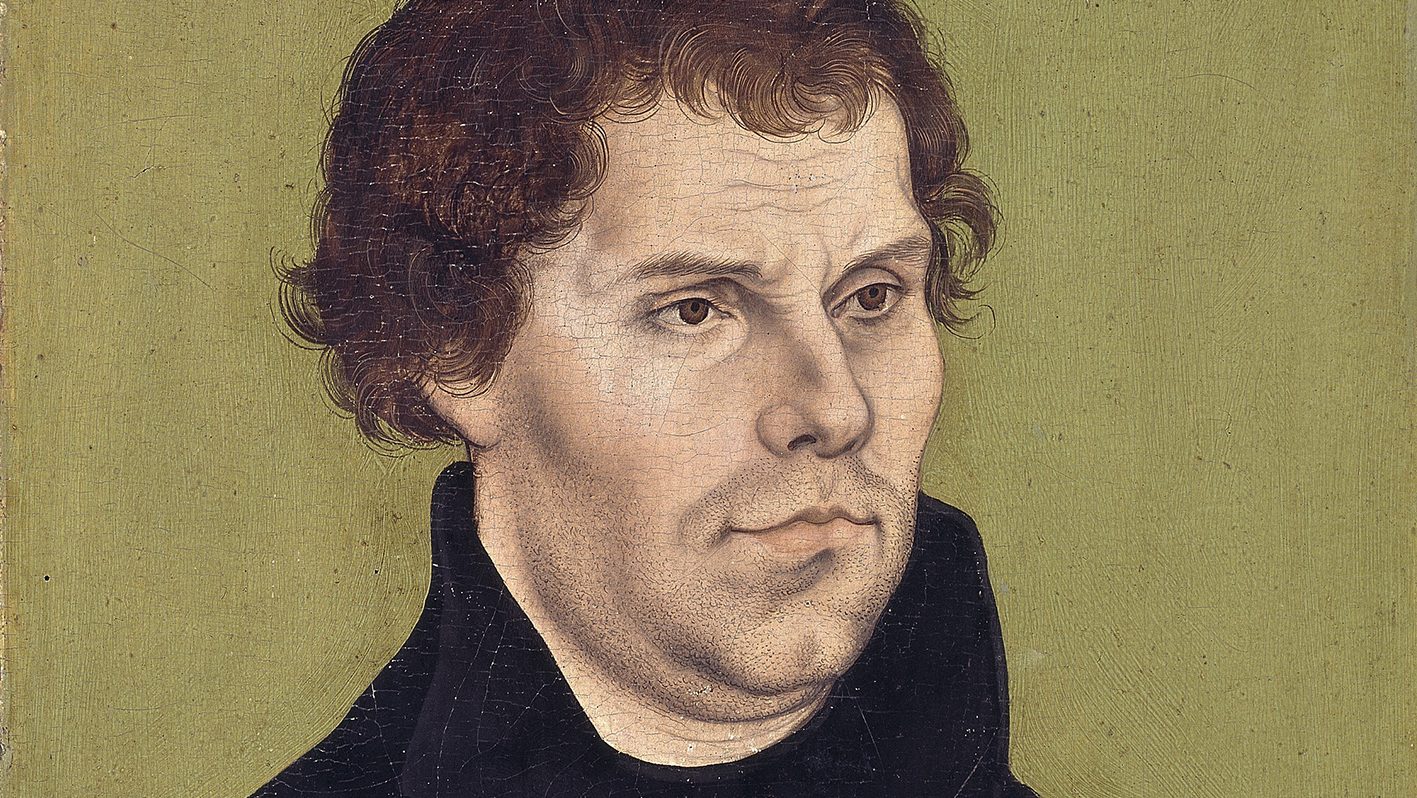

The canon of Sacred Scripture, as set down by the Catholic Church, was unquestioned until the Protestant Reformation. In 1529, Martin Luther proposed an Old Testament of 39 books, made up of the Palestinian canon chosen by the Jewish rabbis in 100 AD. He justified this by citing some concerns that St. Jerome had when he was translating the Old Testament from the Hebrew—that some books in the Septuagint had no extant Hebrew versions. But Jerome did not think that these texts were not inspired, and never proposed to remove them from the canon. The Church always upheld an Old Testament canon of 46 books. In more modern times, the Dead Sea scrolls discovered at Qumran have revealed Hebrew versions of many of these disputed texts from the Septuagint, so they can no longer be contested on those grounds.

Luther really wanted to remove these books from the canon because they conflicted with his theological theories. For instance, 2 Maccabees 12:46 says, “it is a holy and wholesome thought to pray for the dead that they may be loosed from their sins.” This is a direct reference to purgatory, which Luther rejected. Luther even wanted to remove books from the New Testament that did not agree with his theology, such as the epistle of James, and Revelation. But there was no popular support for this, and he was eventually convinced to leave these books in his canon of the Bible.

He did succeed in removing the 7 books not found in the Palestinian Hebrew scriptures, those being Wisdom, Sirach, Judith, Baruch, Tobit, and 1 and 2 Maccabees (and parts of David and Esther). The first English Bible to leave these books out was translated by Miles Coverdale in 1535. He added these books at the end, calling them the “Apocrypha.” This Greek word means “hidden away,” and should not be applied to these texts, which have never been hidden at all. Some Protestant Bibles today leave them out completely, but most include them under this title at the end, or together between the Old and New Testaments. Most Protestants still do not hold them to be inspired as the rest of the Scriptures are.

As Catholics, we can rely on the infallibility of the living, teaching, Catholic Church, to determine which books are indeed inspired by God, and therefore considered part of the Christian canon. As St. Augustine said, “I would not believe in the Gospel, if the authority of the Catholic Church did not move me to do so.”

SOLA SCRIPTURA

Protestant churches follow the doctrine of Sola Scriptura, which means “Scripture Alone.” This doctrine asserts that we are to follow the Bible alone as our sole rule of faith. What this means is that we have to reject Sacred Tradition, and the teaching authority of the Church. As Catholics, we accept the Bible as an authoritative text, but not the only authority on the faith.

First of all, the doctrine of Sola Scriptura not only is not found in the Bible, it is actually contradicted by the Bible! According to the Bible, not everything Jesus said or did is recorded in the New Testament (John 21:25). The Bible also tells us that we as Christians must hold fast to oral tradition and the preached word of God (1 Cor 11:2, 1 Pet 1:25). The Bible also warns us that Scripture can be very difficult to interpret, which implies the need for an authority to interpret these difficult texts for us (2 Pet 3:15-16). Where is that authority found? In 1 Timothy 3:15, we are told that the Church is the “pillar and foundation of truth.”

Indeed, Christ did not come to earth to write a book. He came to earth to found a Church. In the Scriptures, we read that Christ founded a Church with divine authority to govern in His name (Mt 16:13-20, 18:18; Lk 10:16). Christ also promised that this Church would last until the end of time (Mt 16:18, 28:19-20; Jn 14:16).

As you have read in the history above, it was the Apostolic Church, acting with divine authority, that determined what was and was not inspired Scripture. It was not the Scripture that established the Church. We would have no way of knowing what should and should not be trusted as an inspired text if it was not for the teaching of an authoritative Church. Even Luther himself had to admit, “We are obliged to yield many things to the Papists [Catholics]—that they possess the Word of God which we received from them, otherwise we should have known nothing at all about it.”

And we also continue to rely on that Church to help us interpret the Scriptures. A book such as the Bible, that plays such an important role in our faith, cannot be left for free interpretation, open to all. This would result in chaos, with everyone insisting that his or her own reading of the text is the correct one. Indeed, this is largely the reason why there are approximately 30,000 different Protestant denominations in existence today, all believing slightly different things, based on different interpretations of Scripture. Surely this is not what Christ had in mind when he prayed “that they may be one” (Jn 17:20-21).

The Catholic Church rejects the doctrine of Sola Scriptura, relying on Sacred Scripture as well as Sacred Tradition as our rules of faith, and the Church herself as the interpreter of that faith. This is the way it was in all Christendom for 1500 years before the Reformation came about, and the way it still is in the Catholic Church today.

SO WHAT DO CATHOLICS BELIEVE ABOUT THE BIBLE?

The Catholic Church has always held the Bible to be the inspired word of God, and an invaluable teaching tool for our religion. According to the first Vatican Council, “These books are held by the Church as sacred and canonical, not as having been compiled merely by human labour and afterwards approved by her authority, nor merely because they contain revelation without error, but because, written under the inspiration of the Holy Ghost, they have God for their author, and have been transmitted to the Church as such.”

And from the 1952 Papal Encyclical, Provid. Deus, “The Holy Ghost Himself, by His supernatural power, stirred up and impelled the Biblical writers to write, and assisted them while writing in such a manner that they conceived in their minds exactly, and determined to commit to writing faithfully, and render in exact language, with infallible truth, all that God commanded and nothing else; without that, God would not be the author of Scripture in its entirety.”

A full treatment of what the Catholic Church teaches about the Bible can be found in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraphs 101 through 141. The Catechism confirms that “’The Church has always venerated the divine Scripture as she venerated the Body of the Lord’: both nourish and govern the whole Christian life.”

SOME MYTHS ABOUT THE BIBLE

There are several myths and misconceptions about the Bible, and what Catholics believe about it. One of the largest of these is that there were no vernacular translations of the Bible until the Protestant Reformers undertook this task. Though this is far from being true, even those who should know better often repeat it as “fact.”

As an example, let us look at The Illustrated Guide to the Bible, by J. R. Porter, published by Barnes & Noble. Porter, an Anglican, is Professor Emeritus of Theology at the University of Exeter, and served for twenty years as a member of the General Synod of the Church of England. His book can be considered a mainstream text, from a mainstream publisher. In it, he makes the statement, “Protestant versions of the Scriptures led the way, but Catholics soon responded to a demand for Bibles in the vernacular.” This statement implies that Catholics only provided vernacular Bibles after Protestants had already begun this work.

However, this statement of Porter’s does not even agree with his own words written a few paragraphs earlier! He wrote, “from an early period, there were numerous renderings of Scripture into vernacular languages,” and, “In Eastern Europe, the first translations of the Bible into the Slavonic languages were made by the Greek missionaries Cyril and Methodius in the 860s.” One can find many more examples of pre-Protestant vernacular translations of the Scripture. Yet Protestants continue to get credit in the history texts for this innovation.

Let us look at only German translations of the Bible for argument’s sake, as Luther is often credited as being the first one to provide a German version of the Scriptures. History shows us that there were numerous partial translations of the Scriptures into Germanic languages as early as the seventh and eighth centuries. Even more German translations were undertaken in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and a complete German translation was done by the fifteenth—all before the invention of the printing press. In fact, fourteen complete folio editions of the Scriptures in Germanic languages still exist that date from prior to 1522, when Luther translated his New Testament. Similar early examples can be found of vernacular versions of the Bible in nearly all major European languages prior to the Reformation.

Another myth has to do with the “Apocryphal” books mentioned above. In much anti-Catholic literature, it will be stated that the Council of Trent, in 1546, added these books to the Bible. As can be shown historically, this is simply untrue. The Reformers dropped these books, and the Council of Trent, called to uphold Catholic doctrine, simply restated the fact that these books have always been in the Christian canon, since the canon was officially decided upon in the fourth century, and these books would continue to be in the canon.

One more myth, that is all-too often repeated to make the Catholic Church look unbiblical, is that in 1229, the Bible itself was forbidden to laymen and placed on the Index of Forbidden Books by the Council of Valencia. This lie originated in the anti-Catholic book, Roman Catholicism, by Loraine Boettner. Unfortunately, it has been repeated and repeated by other anti-Catholic writers, and even spread into mainstream literature. It is one of the simplest arguments to refute, as it simply cannot stand up to historic scrutiny.

First of all, the Index of Forbidden Books was established in 1543, so a council in 1229 could not have placed a book on it. Second of all, there has never been a church council held in Valencia, Spain. Plus, the Moors were in control of that area in 1229, so the Church could not have had a council there even if they wanted to.

There was a council in 1229, but it was in Toulouse, France. It was a local council, not an ecumenical council (which means it did not represent the entire Church). This council did deal with the Bible, in a way. It was called to address the Albigensian heresy, which maintained that the flesh is evil and therefore marriage is evil, fornication is not a sin, and suicide is not immoral. They also opposed taking oaths, which completely undermined medieval feudal society, which was based on oaths. These Albigensians were using corrupt vernacular versions of the Bible to support their theories, twisting the Bible to “prove” their point. To combat this, the bishops at Toulouse restricted the use of the Bible until this heresy was ended. This was a local restriction, not a universal one, and when the heresy was over, the restriction was lifted.

This restriction never affected more than one area of southern France, and is a far cry from the Catholic Church banning the Bible from all laymen.

While doing some research into the early English translations of the Bible by Wycliff and Tyndale, I came across many references claiming that translating the Bible into English was considered heretical, and that in 1408 a law was enacted that forbade the translation of the Bible into English, and made reading it in English a crime. Like the other “myths” we have examined, there is more to this story as well.

After John Wycliff’s corrupt translation of the Bible (full of Lollard heresy) caused so much confusion and scandal in the church in England, the Church did enact a law, in 1408, that prohibited the unauthorized translation of the Bible into English, and the reading of any unauthorized translation. The goal was to avoid another incident like the Wycliff translation. Under this law, any of the authorized English translations of Scripture before Wycliff were perfectly legal, as would be any future translation into English, done with the permission of Church authority. And of course reading these versions of Scripture was not only perfectly legal, but was in fact encouraged.

APPROVED VERSIONS OF THE BIBLE

To protect this important book and to keep it inerrant, we rely on the infallible Church. In this capacity, the Catholic Church has approved certain versions of the Bible and specifically condemned others. Why is there a need for this?

Since early times, various translations and editions of the Bible have been better than others and some have been specifically in error. This is why the Church commissioned St. Jerome to produce the Vulgate edition in the first place. But with the advent of the printing press, and then the Protestant Reformation, more editions of the Bible were produced, in greater volume than ever before, and many of these were edited specifically to make the Catholic Church and her doctrines appear “unbiblical.” Others have just suffered from poor scholarship.

We have already discussed Martin Luther, and his removal of part of the Old Testament, called the “Apocrypha,” and the fact that he also wanted to remove certain New Testament books that he disagreed with, such as James and Revelation. But Martin Luther, in his German translation, also added things, such as the word “alone” to Romans 3:28, to support his doctrine of salvation by faith alone (which goes against Catholic teaching). Surely a Catholic would be in error to use a translation to which this word (or any word!) has been added. This is but one example of the type of abuse committed against the Bible.

Let us consider for a moment the most beloved of English translations, the King James Version (KJV). King James I of England and VI of Scotland sponsored this version of the Bible. King James was a Protestant king, and a devout anti-Catholic. His authorized translation was geared in many ways to condemn Catholic practices. One obvious example can be found in Matthew 6:7. The KJV reads, “But when you pray, use not vain repetitions, as the heathens do. . .” Many a Catholic has heard this verse quoted as an argument against the praying of the Rosary, which involves repeating the same prayers over and over again.

However, the Greek word that is translated as “vain repetitions” really should be better translated as “to stammer” or “to babble.” What Jesus really is saying in this text is to not ramble on when you pray, but get to the point, say what you mean. He is warning us not to confuse quantity of prayer with quality of prayer. But He certainly did not intend to tell us not to repeat prayers. In fact, Jesus Himself often repeats the same prayer, as in the Our Father.

Consider the circumstances the KJV was commissioned in. During the reign of King James in England, Catholics were forbidden to carry arms, deprived of all rights in court, forced to stay within five miles of their homes, prevented from entering the professions of law or medicine, subject to searches of their homes and persons, had their religious books burned, their devotional items confiscated, were fined for not attending Anglican services, and penalized for not having their babies baptized or their marriages blessed by Protestant ministers. Would you trust a Bible authorized by a man who treated Catholics this way?

During the Protestant Reformation, the Church did authorize an English translation. The New Testament part of this was printed in Reims in 1582 and the Old Testament was printed at Douai in 1609-10. This is called the Douai-Reims translation, and was approved for use by the Catholic Church.

Part of the reason why the Catholic Church insisted on the use of Latin in the liturgies for so long is because Latin, as a dead language, is also a preserved language. The meaning of a Latin word or phrase is the same today as it was 1000 years ago. English, and other vernacular languages, are living, and therefore changing. A phrase in English written today might mean something slightly different 100 years from now, and might be completely misunderstood in 1000 years. Just compare our English to Middle English or Old English! Plus, as you can tell from all of this, the process of translating the text from one language to another opens the door for all sorts of errors, whether purposeful or accidental.

So the Catholic Church takes care authorize modern language Bibles in the vernacular which accurately reflect the meaning of the text. So which English language versions can we rely on? Of course the Douai-Reims is still appropriate. In fact, since it was translated at the same time as the KJV, it has the same poetic language, and those attracted to that in the King James might look to the Douai-Reims for a more reliable version.

A good guide is to use the versions the Holy See has authorized for liturgical use. There are currently three English versions authorized for use in the United States. These are The New American Bible, the Jerusalem Bible, and the Revised Standard Version (Catholic Edition). The New American Bible is the one used in the American Lectionary (where the readings are taken for Mass). The RSV Catholic Edition is the one quoted in the Catechism. Any of these are very appropriate for Catholic use.

There are some versions that have been specifically rejected by the Catholic Church for use at Mass, largely for their use of inclusive language. These are the New American Bible with Revised Psalms and Revised New Testament and the New Revised Standard Version. If you want to determine if any specific version of the Bible can be relied upon, a good litmus test is to look at the first Psalm. It should read, “Happy is the man who follows not the council the wicked,” or some version of that. If it reads, “Happy is the one . . .” or some other gender inclusive term, it should be avoided. This is because the Holy See has rejected this as contradicting the messianic references to Christ in these texts, in which “man” refers not only to David, who wrote the Psalms, but backwards to Adam (the man) and forward to Christ (the Son of Man and the Son of David).

I hope this brief treatment of the Scriptures has shed some light on a complicated issue and enabled people to better understand the place the Bible has in our faith and the Catholic teaching on the Sacred Scriptures. For more reading on the Bible, please see the Catechism of the Catholic Church, Article III, or the following Catholic Encyclopedia articles on line:

From the Catholic Encyclopedia:

The Bible:

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02543a.htm

The Authenticity of the Bible:

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02137b.htm

Editions of the Bible:

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05286a.htm

Inspiration of the Bible:

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08045a.htm

Manuscripts of the Bible:

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09627a.htm