Using Latin in the Latin Rite

There are many different Rites within the Catholic Church. A Rite is a particular way of celebrating the liturgies and sacraments. The great majority of Catholics in the West belong to the Roman Rite, also known as the Latin Rite. In the East there are other Rites, including Coptic, Maronite, and Byzantine. The greatest number of Eastern Catholics practice the Byzantine Rite.

We were fortunate in our parish of St. Mary’s to recently have visiting clergy from the Greek-Ukrainian Catholic Mission of St. Basil in Charlotte celebrate the Divine Liturgy (Mass) in the Byzantine Rite for us. Because the Byzantine Rite is quite different from what western Christians are used to, the celebration was prefaced with a brief talk by one of the Greek-Ukrainian deacons.

At one point he mentioned the fact that the entire liturgy would be celebrated in English. I’m sure that many were relieved to hear that because it meant that they would be able to follow along with the prayers. But there was a sense of disappointment among some. There was an expectation that a Greek-Ukrainian liturgy would involve some Greek or Ukrainian prayers. People were anticipating something different and particular to that culture.

Of course it makes sense that the Greek-Ukrainian Catholic Church would celebrate their liturgies in the vernacular. After all, use of the vernacular is the norm in the Western Church. Why should the East to be any different? I like the vernacular. I like being able to pray in my own language. And as a former English major who has studied the works of Shakespeare and Milton, I know just how beautiful the English language can be. The current translation of the Roman Missal which has been in effect since 2011 especially has some very beautiful English language prayers.

But I also understand the disappointment of those who were hoping to hear a little Ukrainian during the Byzantine Liturgy. There is something about language which is essential to the identity of a particular culture. This is true both inside and outside of the Church. If you drive down the road to Cherokee, for example, you will notice all the road signs are in both English and Cherokee. This is not because there are Cherokee who do not read English. It is to help them preserve their culture, which is also why the Cherokee language is taught in all their schools.

I’m a big Scotophile and I like to keep up with current events there if I can. Currently only about 1% of Scottish residents speak Gaelic. This statistic troubles many in Scotland today, because it means a major part of their heritage is in danger of dying out. And so, as in Cherokee, there are major efforts underway to promote the use of the Gaelic language. The same is true for many minority language groups all over the globe.

Hebrew was chosen as the national language of Israel as a means of promoting national unity and cultural identity after the modern state of Israel was created. This was done even though none of the Jewish people who immigrated into Israel spoke Hebrew as their native language. The modern revival of the Hebrew language was made possible because of this concentrated effort to preserve a cultural identity.

I know several students from immigrant families from Central or South America. A few of them are fluent in Spanish but most are not. Their parents are fluent, but they barely know any Spanish at all. Many of them end up taking Spanish classes in school to help them retain this important aspect of their heritage.

In all the above examples, the use of language as a cultural identifier is very important. The same holds true when it comes to our culture within the Church. We are Catholics of the Latin Rite. What does it mean to be a Latin Rite Catholic who does not know a single Latin prayer? It means part of our heritage is missing.

|

| Second Vatican Council |

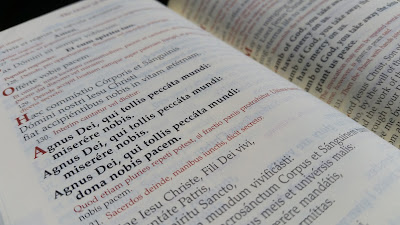

The Second Vatican Council authorized the use of vernacular in the liturgy, but the same council also took great pains to make sure the use of Latin was preserved in the Latin Rite. The constitution on the liturgy which was promulgated by that council plainly states, “The use of the Latin language is to be preserved in the Latin Rite” (Sacrosanctum Concilium 36). While recognizing that it would be beneficial for people to use their mother tongue during the readings and common prayers at Mass, this same document states, “Nevertheless steps should be taken so that the faithful may also be able to say or to sing together in Latin those parts of the Ordinary of the Mass which pertain to them” (54).

The parts of the Ordinary of the Mass which pertain to the people would include the Kyrie, Gloria, Sanctus and Angus Dei, and even the Creed and the Lord’s Prayer. In other words, these are the parts of the Mass which the people say Sunday after Sunday and which are unchanging (except for the Gloria being omitted during penitential times of the year). If there are any parts of the Mass that would be both easy and useful to learn in Latin, it would be these.

In 1974, Pope Paul VI sent copies of a document to every bishop in the world entitled Jubilate Deo, which contained a small selection of the Church’s repertoire of Gregorian chant for the Ordinary of the Mass, chosen for its simplicity. His hope was that every Catholic, no matter their native tongue, would know at least a minimum repertoire of Latin chant. This would enable us to pray in unison not only with our fellow Catholics around the world who speak different languages, but also in unison with all those generations of Catholics who came before us in the past.

Today, in the General Instruction of the Roman Missal (the text that gives instructions on how the Mass is to be celebrated), we are reminded that, “Since faithful from different countries come together ever more frequently, it is fitting that they know how to sing together at least some parts of the Ordinary of the Mass in Latin… set to the simpler melodies” (GIRM 41).

Put very simply, if you are a Latin Rite Catholic (which if you are a Catholic in the West, you probably are), then the Latin language is a part of your heritage. It is a part of your heritage that has been neglected for the past 50 years. But there are many signs that Latin is making a revival in the Latin Rite. Since Pope Benedict XVI issued the letter Summorum Pontificum in 2007, there are now two recognized forms of the Mass in the Latin Rite: the Extraordinary Form, which can only be celebrated in Latin, and the Ordinary Form, which may be celebrated in the vernacular, but for which Latin is still the official liturgical language. The more widespread use of the Extraordinary Form has helped to remind us of the Latin heritage of the Ordinary Form.

Sadly, and for reasons which we need not go into here, in the decades following Vatican II, the use of Latin became something of a shibboleth among Catholics. Either you belonged to one group that wanted only Latin in the liturgy and preferred an exclusive use of the Latin Mass; or you belonged to another group that wanted only English and that had no use for Latin whatsoever. Your love or disdain for Latin identified you as either a traditionalist or a progressive. Try to sneak a bit of Latin into the Mass and you’d be accused of being a closet sedevacantist.

And here is where I am very glad to be working and worshiping with college students. Happily, those of college age today seem to have gotten past this rather unfortunate division. Preference for Latin or English is seen as just that — a preference. In my experience, most college-age Catholics have a general preference for English, as it is the language they know, but think a certain amount of Latin is interesting and even beneficial in creating a sense of piety and reverence in the liturgy. The use of a language we don’t speak or hear every day helps to differentiate our prayer time at Mass as something special and distinctive. The fact that our student choir has on their own chosen to sing parts of the Ordinary of the Mass in Latin (using the Gregorian melodies from Jubilate Deo) is testimony to this shift in attitude.

One other aspect of working with college students is that they arrive at campus from a variety of different places and parishes. Their home parish may use Latin always, sometimes or never. As a general rule, people like what they are familiar with and are uncomfortable with change. (That is certainly true of myself!) Some of our students may have never heard Latin at Mass before, even though they have been worshiping according to the Latin Rite their entire lives.

I have known adults Latin Rite Catholics in their 40s and 50s who have never heard Latin at Mass. To me that is a shame; like the son or daughter of an immigrant who no longer speaks the mother tongue. It means a part of our cultural heritage as Catholics has been lost; a part of our cultural formation has been neglected. I don’t want my students to enter adulthood as Latin Rite Catholics with no experience of praying in Latin. It it is important for Catholics to have at least some passing familiarity with basic Latin prayers and chants. And this is why I am happy to see so many college students participating in its revival in our liturgies.

For those who are interested, here is a run-down of how our Masses on campus are generally celebrated:

- Entrance Antiphon/Hymn: English

- Opening Prayer: English

- Kyrie: Greek

- Gloria: Latin or English

- Collect Prayer: English

- Readings & Psalm: English

- Homily: English

- Creed: English

- General Intercessions: English

- Offertory Hymn: English

- Prayer over the Offerings: English

- Eucharistic Prayer: English

- Sanctus (Holy, Holy): Latin

- Consecration: English

- Mystery of Faith: English

- Lord’s Prayer: English

- Sign of Peace: English

- Agnus Dei (Lamb of God): Latin

- Communion Antiphon: English

- Communion & Post-Communion Hymn: Generally English, sometimes Latin

- Prayer after Communion: English

- Concluding Rites: English

- Recessional Hymn: English