Thinking As God Thinks

22nd Sunday of Ordinary Time (A)

click here for readings

Last Sunday we read in the gospel of how Peter was the Rock upon which Jesus builds the Church. In this Sunday’s gospel, just a few verses later, Jesus rebukes Peter, saying, “Get behind me, Satan!” What happened? Why does Jesus suddenly have such a different attitude about Peter? In truth, Jesus hasn’t changed His mind about Peter. Peter remains the Rock upon which the Church is founded. It is Peter who, in this moment, has changed his mind in that he is no longer thinking like God thinks.

God has a way of shattering our preconceptions. He’s not bound by our expectations. He doesn’t operate according to our rules. As C. S. Lewis said of Him (under the guise of Aslan) in The Chronicles of Narnia, “He’s not a tame lion.”

According to Peter’s thinking, it wouldn’t make sense for Jesus to suffer. He was the Christ, the Messiah, the Son of God. To hear Jesus speaking about His suffering and death scandalized Peter. It went against his own understanding of what sort of Messiah Jesus should be, and so he rebuked Jesus for it. But Jesus is quick to correct Peter. “You are thinking not as God does, but as human beings do.”

This is an interesting contrast to Jesus’ response to Peter’s profession of faith. When Peter proclaims Jesus to be the Messiah, Jesus tells him, “Flesh and blood [i.e. his own human faculties] has not revealed this to you, but my heavenly Father” (Mt. 16:17). Peter in that moment was relying on something greater than his own human reason. He was relying on God’s inspiration.

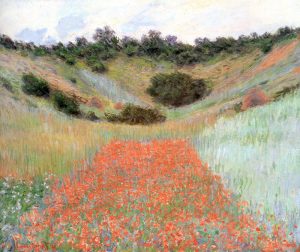

Human reason would not expect a humble carpenter’s son from Nazareth to be the Son of God. Human reason would not expect the Son of God to suffer and die. It’s not that these things are unreasonable. But our finite human perspective put limits on our reason. We can only see so far. We are only ever aware of part of the puzzle. God, on the other hand, sees things from the perspective of eternity. So very often, what doesn’t make sense for us makes perfect sense from God’s point of view. If you’ve ever looked at an impressionist painting you have a sense of what I mean. Look too closely at just one part of the painting and all you will see are colored dots. Step back and look at the whole painting and you can see how each dot of color was specifically placed by the artist to create a beautiful landscape. When it comes to the landscape of the Universe, as well as our individual stories within it, only God can see the big picture.

So it’s not surprising that we struggle often to understand God’s plan. This is especially true when it comes to suffering and pain. We perceive any kind of suffering as bad — even evil. We have a hard time understanding how a good and loving God, who is also all powerful, can create a world in which good people suffer. When we experience or witness suffering, it can cause us to doubt God’s goodness, His omnipotence, or even His very existence. How can a good God allow suffering?

When we say, “I don’t believe in a God who would allow X to happen,” what we really mean is, “If I were God I’d do things differently.” But who are we to judge God’s actions? Who are we to criticize His plan? Did we speak the world into being? Did we set the stars in their place? Do we control the orbits of the planets? Did any of us create ourselves in our mother’s womb? Most of us struggle to plan our weekends. And we dare to judge God because He doesn’t run the Universe the way we think it ought to be done.

Even from our limited human perspective we know that not all suffering is bad. When a doctor administers radiation or chemotherapy to a cancer patient, it causes the patient suffering. But the suffering is necessary for the sake of healing. When a parent disciplines their child, it causes suffering for the child. But it is for the loving purpose of teaching the child a lesson, and to help him or her become a better person. It also causes the parent suffering, but he or she is willing to accept the suffering for the sake of their child’s well being. If we can see how, even on a human level, suffering can sometimes be necessary to bring about a greater good, then we should be able to accept that God can bring good out of suffering in ways we simply can’t perceive.

The people of ancient Israel expected a Messiah to come and alleviate their suffering. They didn’t expect God Himself to be that Messiah. And they certainly didn’t expect God to suffer Himself not only for their sake, but the sake of all mankind. It is understandable, from a human point of view, that Peter would reject Jesus’ teaching that He would suffer and die. What Peter needed was a divine point of view.

How do we get there? We cannot climb to the highest heavens to see the Universe as God sees it. We cannot peek into eternity and see the “big picture” of how our lives play out in God’s divine story. So our journey must begin with humility. We must recognize that we don’t know everything. We must recognize that we cannot figure it all out on our own. Only then are we able to be taught. Then we must trust God to teach us.

Many times, if we are patient, and open to the work of the Spirit in our lives, we can come to understand how a period of suffering was for our good. Perhaps it taught us an important lesson, helped us to grow in virtue, or gave us the strength needed to endure a tougher trial later on. God sees our lives from the perspective of eternity, and if we come to Him humbly in prayer, He may offer us a glimpse of divine understanding. He may allow us to see part of the bigger picture.

But sometimes we don’t get to know these things. We don’t know why the young child suffered from that terminal illness. We don’t know why our loved one suffers from mental depression. We don’t know why so many lost their homes in a hurricane. We just don’t know. Humility allows us be at peace in our not knowing. We don’t have to understand God’s plan to know that He has a plan.

We don’t have to understand God’s plan to trust that He is good, and loving, and in control. God knows what He is about, even if we don’t. The popular phrase today is “God don’t make junk!” Blessed John Henry Newman said it more eloquently in 1848 in his Meditations and Devotions.

God knows me and calls me by name…

He has committed some work to me which He has not committed to another.

I have my mission — I never may know it in this life,

but I shall be told it in the next.

Somehow I am necessary for His purposes…

I have a part in this great work…

He has not created me for naught…

Therefore I will trust Him.

Whatever, wherever I am,

I can never be thrown away.

If I am in sickness, my sickness may serve Him;

In perplexity, my perplexity may serve Him.

If I am in sorrow, my sorrow may serve Him.

My sickness, or perplexity, or sorrow may be necessary causes of some great end,

which is quite beyond us.

He does nothing in vain;

He may prolong my life,

He may shorten it;

He knows what He is about.

He may take away my friends,

He may throw me among strangers,

He may make me feel desolate,

make my spirits sink, hide the future from me —

still He knows what He is about…

When we struggle to understand why we or those we love experience suffering; when we struggle to make sense of tragedies and natural disasters; when we struggle with not knowing God’s plan for our lives, let us remember to trust Him. Trust in His goodness. We do not think how God thinks. His ways are not our ways. We cannot see the whole picture. But we can have faith that our lives are a part of a divine work of art that we will one day perceive from the eternal perspective of heaven.