The Command to Love

30th Sunday in Ordinary Time (Year A)

“Teacher, which commandment in the law is the greatest?”

Matthew 22:36

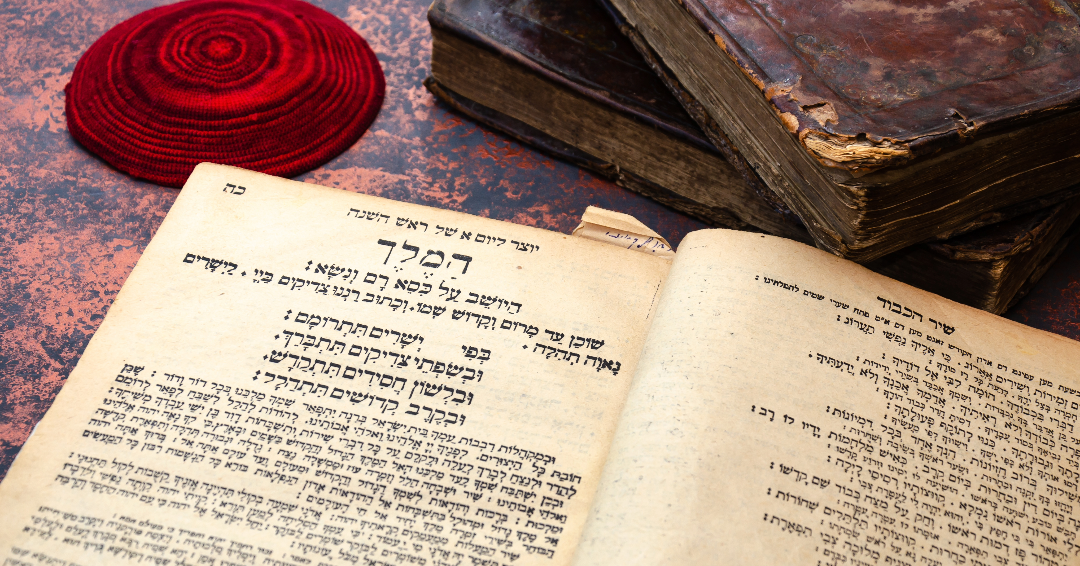

In this Sunday’s gospel (Mt 22:34-30), a scholar of the law poses a question to Jesus: “Which commandment in the law is the greatest?” Scripture scholars at that time would often debate which of the many commandments in the Torah, or the Books of the Law (the first five books of the Hebrew scriptures) were greater and therefore should take precedent over the others.

Jesus answers the question by quoting not one but two of the laws of the Old Testament. The first is what is called the Shema, the command to love the Lord your God with all your heart, all your soul, and all your mind found in Deuteronomy 6:4-5. Then Jesus identifies the second greatest commandment as “to love your neighbor as yourself,” quoting Leviticus 19:18. All the rest of the law depends upon these two, he says.

What are we to make of Jesus’ summation of the law? There are two ways to get it wrong. One is to think Jesus is making things easy for us by dismissing the old, rigorous laws and replacing them with a new and easy law of love that amounts to “just be nice to each other.” The other way is to think Jesus is making things impossible for us by commanding that we always have good, affectionate feelings toward everyone — something we know from experience that we are not capable of doing.

Both of these interpretations suffer from the same flaw; they assume love to be an emotion, and we can’t choose what emotions we do or do not feel. But the very fact God commands us to love tells us that love means something more. Love is not a feeling. It is something we can choose to do (or not to do). So what does it mean to love? According to St. Thomas Aquinas, it means “to will the good of another” (CCC 1766). Regardless of how I may feel about a person, I can still choose to desire their good and actively work towards that end. That’s love.

In identifying these two greatest commandments, Jesus is teaching us how to properly order to our love. The One whom we should love first above all others is God because God is more lovable than anyone or anything else. God is love (1 Jn 4:8) and therefore infinitely worthy of love. After God, I should love my neighbor as myself because my neighbor is equally worthy of love as I am. We are both made in the image and likeness of the God who is love (cf. Gen 1:27). So to love God more than anything and your neighbor as yourself is the only right and just way to love.

The rest of the commandments are meant to help us live out the primary command to love. Since love is not an emotion, but something we choose to do, it follows that there is a right way and a wrong way to do it. So it’s important to ask, how do I love? What does real love look like?

Consider the Ten Commandments. The first three tell us what it means to love God. To love God with all your heart, mind and soul means, at a minimum, not worshiping other gods. It means respecting God’s name and not using it in vain. And it means prioritizing our time to ensure we give Him proper worship. Loving God means more than this, but it means at least this. So this is where we begin.

The final seven commandments teach us what it means to love our neighbor. If you love your neighbor, you don’t lie to him, steal from him, commit adultery against him, or kill him. Of course loving your neighbor means more than this, but it means at least this. Obeying the commandments is a start, because the things prohibited by the commandments are incompatible with love.

All the other moral commands found in the Bible extrapolate and build upon the Ten Commandments in the same way that the Ten Commandments extrapolate and build upon the two greatest commandments. For example, the commands about how we are to treat the poor and vulnerable we find in this Sunday’s first reading from Exodus 22 build off of the commandment against stealing. To refuse to help someone in need when you have the means and ability to do so is the equivalent of stealing from them.

We only realize this if the interpretive key we are using to understand the commandments is love. The law without love is reduced to rigorism. (“I’m not taking their property so technically it’s not stealing; I have no legal obligation to help them”). Love without law is reduced to mere emotion. (“If one of you says, ‘Go in peace; keep warm and well fed,’ but does nothing about their physical needs, what good is it?” (Jas 2:16)).

Why does all this matter? Why is Jesus so concerned that we love one another? It’s not from some ambiguous humanitarian concern for “the common good,” but because our Lord truly loves us and therefore desires our good. And our greatest good is to be holy — to be like God — and God is love. By loving rightly we become more like the God in whose image we are made, and therefore our most authentic selves.