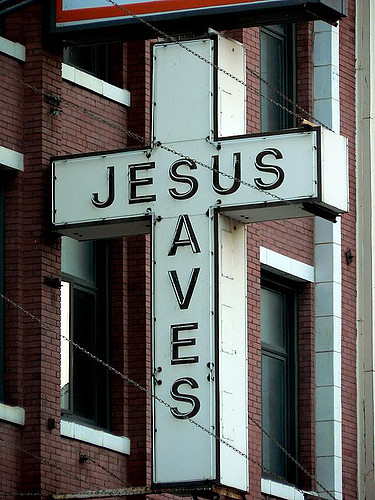

Jesus Saves

12th Sunday of Ordinary Time (A)

click here for readings

Jesus saves. That’s what you see written on countless hand painted signs along the side of the highway across the south. It’s tempting for us to smile and roll our eyes at this particular brand of home-spun Protestant piety, but we shouldn’t be too smarmy about it. If you were to summarize the gospel message in just two words, those would be them. Jesus saves.

His grace has strengthened me until now and made me content to lose goods, land, and life as well, rather than to swear against my conscience… By the merits of His bitter passion joined to mine and far surpassing in merit for me all that I can suffer myself, His bounteous goodness shall release me from the paints of purgatory and shall increase my reward in heaven besides.

I will not mistrust Him, Meg, though I shall feel myself weakening and on the verge of being overcome with fear… I know this well: that without my fault He will not let me be lost. I shall, therefore, with good hope commit myself wholly to Him…

[T]herefore, my own good daughter, do not let your mind be troubled over anything that shall happen to me in this world. Nothing can come but what God wills. And I am very sure that whatever that be, however bad it may seem, it shall indeed be the best.

What struck me as I read St. Thomas More’s words to his daughter was that More was not willing to die for a “cause.” More was willing to die for Christ, because he knew — and knew deeply — that to die with Christ is to rise to new life.

More knew deeply the words that Jesus preaches in today’s gospel. “[D]o not be afraid of those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul; rather, be afraid of the one who can destroy both soul and body in Gehenna” (Mt 10:28). Jesus goes on to say that he will acknowledge before the Father those who acknowledge Him, but that He will deny those who deny Him.

More knew that to deny his conscience, to deny deny his faith, to deny Christ, would be the true death sentence. Doing so may allow him to enjoy life in this body for a little longer, but his soul would be dead. Only by staying true to his faith and publicly acknowledging Christ, even and especially by his own death, would he gain eternal life in heaven.

St. Thomas More could do this, because he knew well what the roadside signs still proclaim today: Jesus saves.

We see those words plastered everywhere. But do we believe them? Do we believe them as much as St. John Fisher, St. Thomas More, and all the other martyrs willing to die before they would deny Christ or His Church? Are we willing to stand against the rising tide of the world that insists our faith is a fairy tale and the Church’s moral teachings are outdated and irrelevant? That the Church should change her teachings or get out of the way?

Most of us, thankfully, are not threatened with death if we don’t “get with the program” and deny the teachings of the Church. Most of us are threatened only with mild inconvenience and perhaps a certain amount of social stigma. But there may come a time when we will be asked to sacrifice much more. Will we be ready?

Ironically, our lives depend upon our willingness to give them up. And there is only one thing that can make us face that possibility with peace, dignity, and hope. That is a sure and abiding trust in God — a certain knowledge that yes, Jesus does save. By remaining true to Him who conquered death, death becomes for us only a portal to our final redemption; the gateway to eternal life.